In 2000, Asia was home to 61% of the earth’s population and accounted for just 37% of its carbon emissions. In 2021, the figures were 59% and 58%.

Climate change has profound impacts on a wide variety of human rights, including the rights to life, self-determination, development, food, health, water and sanitation, and housing.

The region’s explosion in greenhouse gases

While once Asian officials could credibly argue that GHG emissions of other regions dwarfed theirs, the world has changed. In 2000, Asia was home to 61% of the earth’s population and accounted for just 37% of its carbon emissions. In 2021, the figures were 59% and 58%, respectively. Put another way, while the rest of the world in aggregate cut emissions by 700m tonnes of carbon over that period, Asia saw a rise of 12.4bn. From low-value manufacturing to high-tech factories, fossil fuels remain the energy driving the region’s bustling economies.

Figure 1: Asia is the source of most of the world’s CO2 emissions

Annual emissions from fossil fuels and industry emissions (in billions of tonnes)

Source: Our World in Data, 202311

Figure 2: Asia is responsible for more than half of all CO2 emissions

Annual emissions from fossil fuels and industry emissions (in billions of tonnes)

Source: Our World in Data, 202312

The higher emissions in Asia stems from its reliance on oil and, especially, coal in its race to develop.

Figure 3: Asia’s per capita CO2 emissions are roughly equivalent to the global average Annual emissions from fossil fuels and industry emissions (tonnes)

Source: Our World in Data, 202313

The higher emissions in Asia stems from its reliance on oil and, especially, coal in its effort to create jobs, reduce poverty and reach new levels of prosperity.

This contrasts sharply with other regions. In developed G20 states, coal power’s share of electricity generation halved between 2000 and 2020, from 39% to 19%. In developing G20 members - including China, India and Indonesia - it grew from 48% to 53%.14 During that period, China opened new coal power plants capable of producing nearly 1,000 gigawatts (GW) in total.15 India was responsible for only around 180 GW of new coal-fuelled capacity, but this too still exceeded all other countries in Asia. Moreover, India gets three-quarters of its electricity from coal, and this is soon to be supplemented by 39 new plants.16 Thus, looking ahead to 2031, despite a shift toward gas and renewables in some economies, coal will remain a major component of Asia’s energy mix.

1,000 gigawatts

Between 2000 and 2020, China opened new coal power plants capable of producing nearly 1,000 GW in total.

Figure 4: Coal will remain a major component in Asia’s electricity mix despite losing share to gas and renewables by 2031

(domestic power generation by source; % of total)

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit, 202217

Climate-related physical and economic challenges that will require attention

Even while Asia is now contributing to carbon emissions at the same per capita rate as the global average, climate change exposes the region to unique public health and economic risks. Fossil fuels bring air pollution in addition to excess carbon. According to a 2019 study, in India, airborne impurities kill more than 1.5m people each year, accounting for nearly a fifth of all fatalities18 while the WHO reports that a similar number of Chinese nationals die annually from ambient air pollution.19

1.5m fatalities each year

According to a 2019 study, in India, airborne impurities kill more than 1.5m people each year, accounting for nearly a fifth of all fatalities.

Deadly levels of heat have also tripled worldwide since the 1980s, and now affect nearly a quarter of the world’s population.20 The issue is at its most extreme heat in South Asia.21 Though affluent populations can shield themselves from the problem, in a heatwave “the economically insecure are pushed to the front lines”,22 according to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). And with around 600m people in Asia living in informal settlements,23 not to mention hundreds of millions more in low-income formal settings, the toll from heatwave-induced public health crises may be significant.

Asian economies equate to two-thirds of global GDP vulnerable to productivity losses from excess heat and humidity.24Agricultural workers are expected to account for 60% of working hours lost globally to heat stress.25 Those in the least developed countries - including many in Asia - are among the most impacted by exposure to extreme temperatures, already bearing almost half of the estimated 295bn work hours lost due to heat in 2020.26

Two-thirds

Of GDP around the world that is vulnerable to productivity losses from excess heat and humidity, more than two-thirds is from Asian economies.

Figure 5: Working hours lost to heat stress, by sub-region, 1995, with projections for 2030 (%)27

Source: International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2019

Flooding will take its toll on the region as well. Nearly 600m people in Asia live in low-lying coastal regions, with Asia home to 11 of the 15 most endangered cities worldwide.28 According to Greenpeace29 rising sea levels could inflict US$724bn in economic damage on seven of Asia’s major cities this decade. By 2050, the Asia-Pacific region may lose about US$1.2trn each year in capital stock (factory plants, equipment, and other assets) due to climate-change-induced flooding alone. Some industries will be disrupted more than others. For example, by 2030, many of Asia’s current apparel and footwear factories - including over half of those in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam - are expected to be underwater due to their position near sea level in low-lying areas.30 The map below is but one of many scenarios available depicting how sea level rise might impact the apparel industry in both Vietnam and Bangladesh.

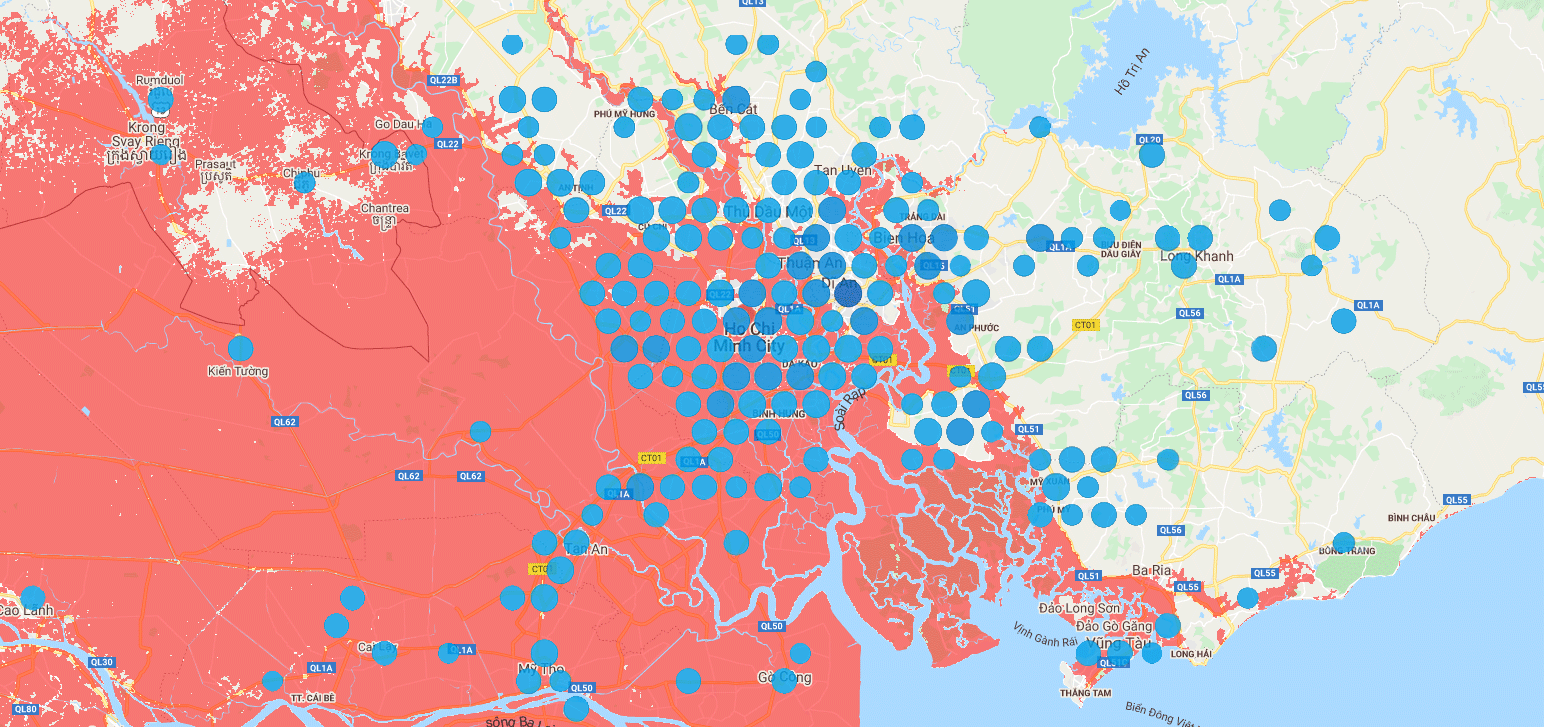

Figure 6: Projected sea level rise in Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam by 2030

Smaller-scale suppliers sitting in the flood risk area will be most impacted by rapid increases in sea-level rise

Source: Cornell Global Labor Institute, 2021

Note: Blue circles represent clusters of factories with darker blue circles indicating greater factory density.

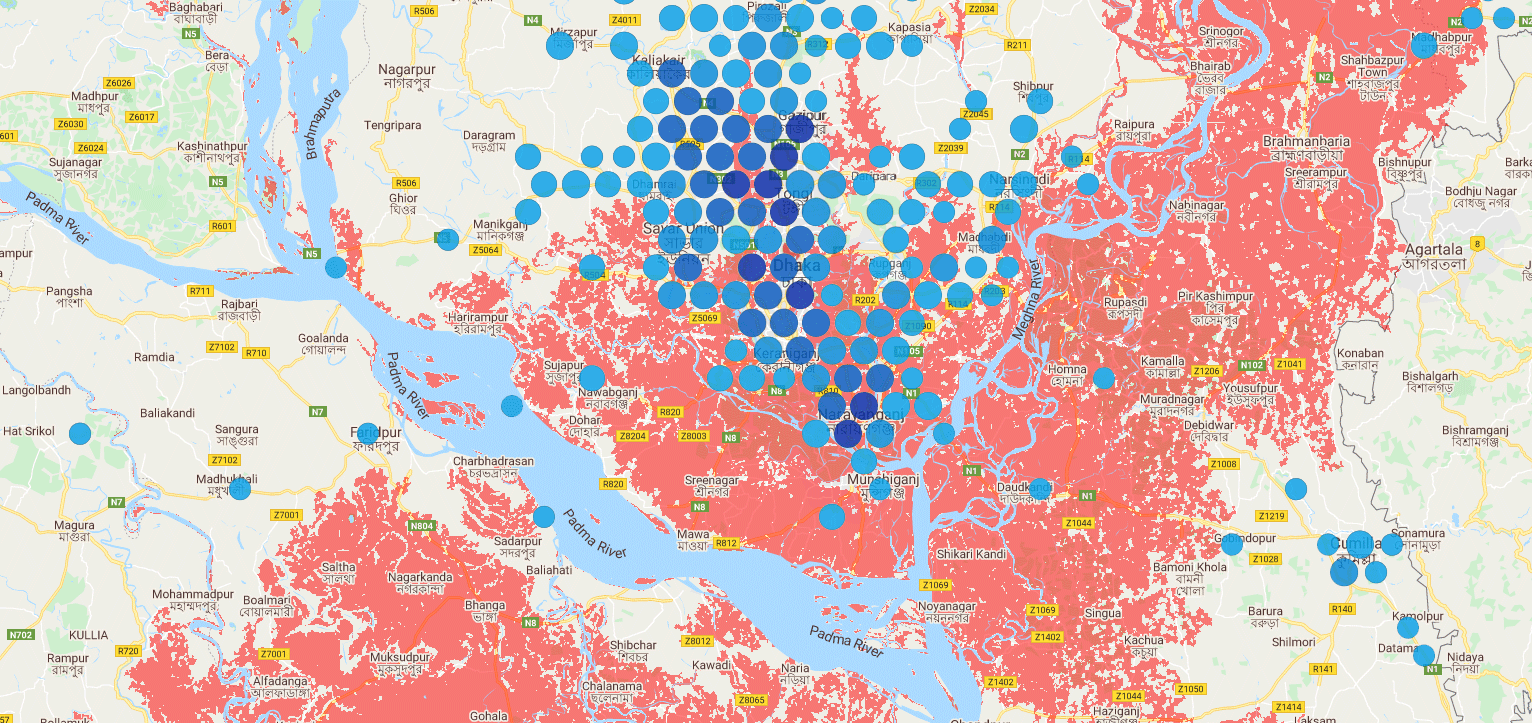

Figure 7: Projected sea level rise in Dhaka, Bangladesh by 2030

Smaller-scale suppliers sitting in the flood risk area will be most impacted by rapid increases in sea-level rise

Source: Cornell Global Labor Institute, 2021

Note: Blue circles represent clusters of factories with darker blue circles indicating greater factory density.

New legal risks

The increasing recognition of the links between climate and human rights is also changing the risk profile in Asia for companies and for governments. In a May 2022 report, the Philippines Commission on Human Rights argued that the world’s most polluting companies have an obligation to address the harms of climate change. It found that 47 of the world’s biggest coal, oil, mining and cement firms engaged in “wilful obfuscation” of climate science and that, by blocking a global transition to clean energy, such actions were “at the very least immoral.” It added that these companies had arguably breached existing laws in the Philippines and might serve as the basis for legal liability in other countries.

Wilful obfuscation

47 of the world’s biggest coal, oil, mining and cement firms engaged in “wilful obfuscation” of climate science, blocking the global transition to clean energy.

- Philippines Commission on Human Rights, May 2022 reportWhile the report only represents a potential legal argument rather than a binding decision, it does point to the growing volume of climate litigation. Catherine Higham, policy fellow for Climate Change Laws of the World at the LSE also writes that those at the nexus of climate change and biodiversity are increasingly focussing on legal recourse to compensate for loss and damage resulting from climate change.31

Those at the nexus of climate change and biodiversity are increasingly focussing on legal recourse to compensate for loss and damage resulting from climate change.

- Catherine Higham, policy fellow for Climate Change Laws of the World at the LSE

Over 2,000 climate litigation cases have been recorded by Climate Change Laws of the World, a database operated by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. In Asia, climate litigation has been less well documented, however, although this could result from a lack of data collection on actual cases rather than a dearth of cases. “It may also be due to differences in approach, whereby cases are less explicitly focused on climate change but nonetheless may have significant impacts for climate action,” adds Ms Higham.

The climate litigation that has occurred in Asia has focused on both state failures to implement policy and on companies that have committed environmentally-linked, human rights torts.32 These efforts appear to be having an effect: in 2022, IPCC recognised its impacts on “the outcome and ambition of climate governance.” Ms Higham and her colleagues agree, adding that “climate litigation has been successfully used as a tool to influence governance in the absence of political action.”

Over 2,000 climate litigation cases

Over 2,000 climate litigation cases have been recorded by Climate Change Laws of the World.

These lawsuits are not a silver bullet, however. It may be difficult to prove beyond reasonable doubt that these firms are liable for climate impacts, notes Mr Bueta. “Most of these groups are civil society organisations, grassroots organisations. They do not have enough resources to show initial evidence of the harm or danger they are alleging from a certain activity or project.” Ms Higham further finds that any success of climate litigation to date “doesn't mean that political action couldn't be a more effective and more efficient way of dealing with some of these issues.”

Figure 8: Number of climate litigation cases (global 1993-2021)

Source: Climate Change Laws of the World, LSE, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 2022

Even while they face a rising number of climate-related lawsuits, companies operating in Asia also need to be aware of the growth in relevant extraterritorial rules that may apply to their activities. “More states, or supranational bodies, like the EU, are thinking about how we turn what has been a set of voluntary standards and principles into mandatory regulations that apply across the board,” says Ms Higham.

Companies exporting various commodities to the bloc, including palm oil, beef, timber, coffee, cocoa and soy, will have to provide relevant due diligence declarations.

Two examples demonstrate this. First, the European Commission has proposed a corporate sustainability due diligence directive (CSDDD), which will require businesses to prevent, and where necessary remedy, adverse human rights impacts for which they are responsible. An ostensible exemption for suppliers with fewer than 250 employees is unlikely to leave smaller firms unaffected by the directive as larger companies will insist on having relationships only with smaller firms that prioritise sustainability. More importantly, the directive would also require companies to be more transparent about their human rights and environmental due diligence processes, and to engage with stakeholders, including employees, customers and investors, to build a more sustainable and responsible business.

The European parliament, meanwhile, approved a landmark deforestation law on 20 April 2023 to ban imports into the EU of coffee, beef, soy and other commodities if they are linked to the destruction of the world’s forests, an issue that strongly overlaps with climate change. Deforestation is responsible for about 10% of global GHG emissions that drive climate change. The law will require companies that sell goods into the EU to produce a due diligence statement and "verifiable" information proving their goods were not grown on land deforested after 2020, or risk hefty fines.33

Implications of treating a healthy environment as a human right

The UN General Assembly’s recognition of a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a universal human right has strong symbolic and political value. But indeed, international jurisprudence had already been moving in this direction, even before the UNGA resolution. In October 2022, a case brought by Torres Strait Islanders claimed that the Australian government had failed to take mitigation and adaptation measures to combat the effects of climate change and had therefore failed in its duty to protect human rights. The UN Human Rights Committee agreed, finding that the Australian Government had violated islanders’ rights by failing to implement adaptation measures to protect homes, private lives and families.34

The UN Human Rights Committee agreed that the Australian Government had violated islanders’ rights by failing to implement adaptation measures to protect homes, private lives and families.

Complicating matters for states, efforts to mitigate climate change may also be accompanied by human rights abuses.

The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre has recorded a rise in human rights abuses in the context of renewable energy projects worldwide. Its 2021 analysis of the human rights policies and practices of 15 of the largest global renewable energy companies found “profoundly concerning” results with poor scores overall. About 200 allegations of abuse of land rights and Indigenous Peoples' rights – including displacement, violence and intimidation – have been recorded by the centre since 2010.35 In Asia, the livelihoods of river and riverside communities continue to be threatened by the construction of hydroelectric projects. In the Mekong River, which runs through East and South-East Asia, some 11 dams on the main river and 120 tributary dams are planned for hydropower generation, which scientists have warned will imperil the already fragile river system and hurt communities dependent on fishing and farming.36

“Profoundly concerning”

The human rights policies and practices of 15 of the largest global renewable energy companies found “profoundly concerning” results with poor scores overall.

- The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, Berlin, 2021 analysisAffected communities argue that the dams will flood their ancestral lands, threatening their livelihoods, culture and identity.37 In India, large solar projects, among others, are exempt from environmental assessment and public hearings. Farmers in some regions allege that renewable energy companies are seizing agricultural lands for solar plants.38 “In environmental circles, it is accepted that green projects might actually be used for green grabs of land, displacing vulnerable communities and taking advantage of marginalised sections of populations. And, unfortunately, there hasn't been much progress in developing a good framework around it,” says one climate expert in India.

Download the report

Access the footnote sources, appendix information and charts by downloading the full PDF report

Written by